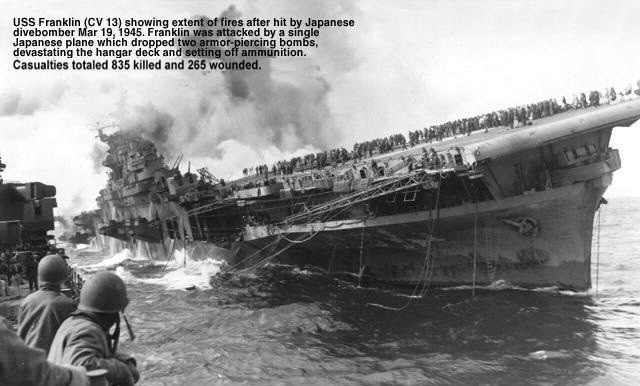

Before dawn on 19 March 1945 the U.S.S. Franklin, who had maneuvered closer to the Japanese mainland than had any other U.S. carrier during the war, launched a fighter sweep against Honshu and later a strike against shipping in Kobe Harbor. Suddenly, a single enemy plane pierced the cloud cover and made a low level run on the gallant ship to drop two semi-armor piercing bombs. One struck the flight deck centerline, penetrating to the hangar deck, effecting destruction and igniting fires through the second and third decks, and knocking out the combat information center and airplot. The second hit aft, tearing through two decks and fanning fires, which triggered ammunition, bombs and rockets. The Franklin

, within 50 miles of the Japanese mainland, lay dead in the water, took a 13° starboard list, lost all radio communications, and broiled under the heat from enveloping fires. Many of the crew were blown overboard, driven off by fire, killed or wounded, but the 106 officers and 604 enlisted who voluntarily remained saved their ship through sheer valor and tenacity. The casualties totaled 724 killed and 265 wounded, and would have far exceeded this number except for the heroic work of many survivors. Among these were Medal of Honor winners, Lieutenant Commander Joseph T. O'Callahan, S. J., USNR, the ship's chaplain, who administered the last rites, organized and directed firefighting and rescue parties, and led men below to wet down magazines that threatened to explode, and Lieutenant (junior grade) Donald Gary who discovered 300 men trapped in a blackened mess compartment, and finding an exit, returned repeatedly to lead groups to safety. The U.S.S. Santa Fe(CL-60) similarly rendered vital assistance in rescuing crewmen from the sea and closing the Franklinto take off the numerous wounded.

The Franklin was taken in tow by the U.S.S. Pittsburgh until she managed to churn up speed to 14 knots and proceed to Pearl Harbor where a cleanup job permitted her to sail under her own power to Brooklyn, N.Y., arriving on 28 April. Following the end of the war, the Franklinwas opened to the public, for Navy Day celebrations, and on 17 February 1947 was placed out of commission at Bayonne, N.J. On 15 May 1959 she was reclassified AVT 8.

TheU.S.S. Franklin received four battle stars for World War II service.

The Franklin was taken in tow by the U.S.S. Pittsburgh until she managed to churn up speed to 14 knots and proceed to Pearl Harbor where a cleanup job permitted her to sail under her own power to Brooklyn, N.Y., arriving on 28 April. Following the end of the war, the Franklinwas opened to the public, for Navy Day celebrations, and on 17 February 1947 was placed out of commission at Bayonne, N.J. On 15 May 1959 she was reclassified AVT 8.

TheU.S.S. Franklin received four battle stars for World War II service.

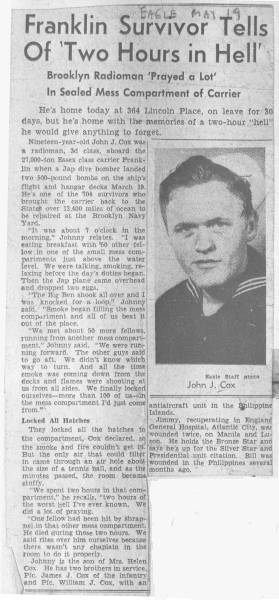

Uncle Johnny served on the USS Franklin as a Radioman

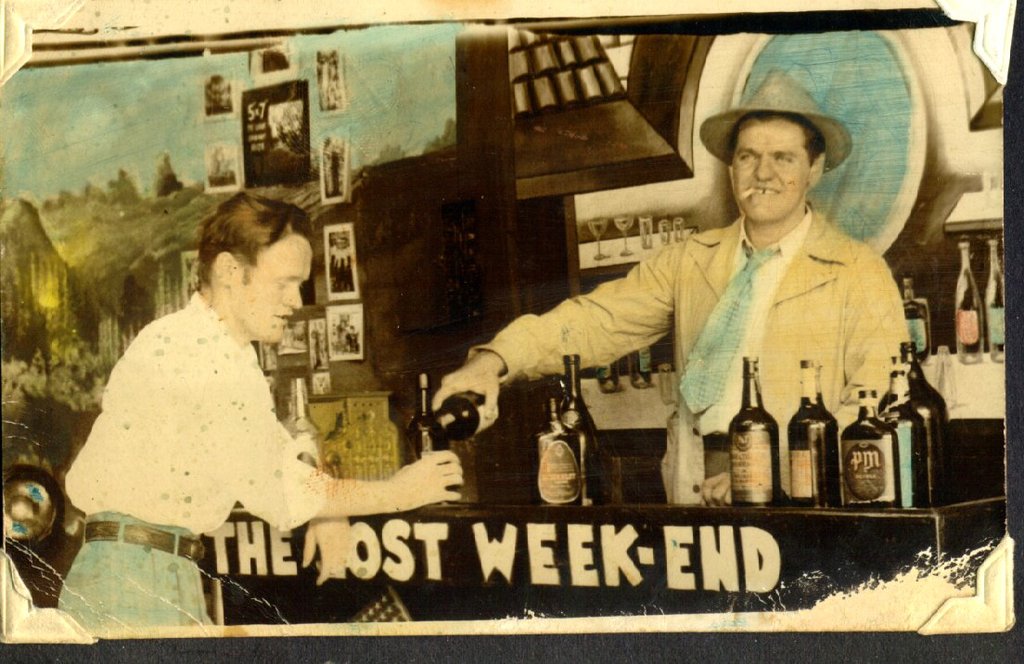

Dad and Uncle Johnny Shortly After The War

The Japanese had bombed Pear Harbor in 1941 when I was 15 years old and most of my older friends had already enlisted in some branch of the military so I was left alone and pining to get into it. My two brothers had already responded to Uncle Sam's 'Greetings' so when I turned seventeen, and was afraid the war would be over before I could get into it, I went on a six-month-long crusade to persuade my mother to give her consent to my enlisting in the Navy Reserve. She finally she agreed and gave her written consent so off I went to Newport, Rhode Island for "Boot Camp' which entailed six weeks of training in seamanship and a regimen of physical training that was a breeze for me thanks to the many hours of gymnastics. For the first time in my life I enjoyed three square meals a day (with meat which was seen only on special occasions in our family) and piled on seventeen pounds of extra muscle. After "boots' I was assigned to a Bainbridge, Maryland radio-operating school where I learned Morse code and the other skills of a radio operator. Then there was an interminable 5-day cross-country troop-train ride to California and eventual assignment to the U.S.S. Franklin (CV13) which was an Essex-Class aircraft carrier, built at Newport News in Virginia and launched on the 14th of October 1943. In recognition of the ship's size and power t Ben'. It had a displacement of 27,000 tons, an overall length of 872 feet, and a beam of 93 feet. It carried around 70 aircraft of various types from "fighter planes' to "torpedo planes'. It was armed with twelve 5-inch guns plus a number of dual 40mm anti-aircraft guns as well as a number of 20mm guns for close defense. It was the temporary home of between 2800 to 3000 enlisted men and officers.

I arrived aboard the ship on May 29 1944 and became a member of the radio crew that stood watch in the main radio shack where I would be spending much of my future time copying code that would direct the operations of the ship and to some extent the operations of the entire fleet. The main radio shack was located in the ships Island and was only about 15 feet from two twin-mounted five inch guns that came to an incredibly noisy life during enemy attacks making it necessary for the job of copying of code to become a special kind of art. We had to cover one of the earphones with one hand and hold it tight to one ear to try to drown out the noise of the guns while typing with the other hand. And when we were close to enemy-held islands the Japs would zero in on our radio frequency and transmit what became known as "bag-pipes' which were loud noises that resembled Scottish bagpipes aimed at disrupting communications. So we spent a lot of time holding an earphone close to one ear with one hand and typing code with the other.

A short time after my arrival aboard ship in California we headed for Honolulu where we enjoyed a short "liberty' and by the 4th of July 1944 both Big Ben and I had experienced our baptism of fire. With some discomfort I discovered that aircraft carriers were very popular with Japanese pilots and Ben was no exception. They aimed their bombs at him in preference to most other ships and some even tried to crash-dive on him. Some bombs landed and one plane crash dived on him but he was a tough nut to crack and no matter what they did they just couldn't sink him. He always came back for more. It may sound strange to hear me call a ship a "him' instead of a "her' - sailors always attribute human qualities to their ship although they usually think of it as a "she'. But in my eyes Big Ben was too tough to be a "her'. I've never been a misogynist – I've loved as many women as I could and as often as I could when I was young – but there was nothing feminine about Ben.

Our pilots were supermen, we ranged all over the Pacific creating as much havoc as possible and they were like mad hornets stinging anything that was Japanese whether ships, planes, enemy airfields, or troops. The official record shows that we celebrated the 4th of July 1944 by taking part in strikes against targets in Guam, and followed this by visiting Iwo Jima, Haha Jima and Chichi Jima in the Bonin and Volcano Islands. Then we turned our attention to Rota and again to Guam in the Marianas Islands. A week later we hit Yap and Ulithi in the Palau Islands and on the 22nd of July we went back to Guam to support the invasion. In August our pilots attacked shipping in the Bonin and Volcano Islands. In October we hit Luzon in the north of Philippine Islands and Tainan on the Island of Formosa, followed by supporting the invasion of Leyte in the Philippines. Towards the end of October we hit targets in Manila Bay and joined in with the rest of the fleet in the Second Battle of the Philippine Sea. Whenever Japanese planes threatened the ship our pilots intervened and dealt out fierce punishment but when they went on a mission we were on our own. When the cats away the mice will play and as the task force ventured ever closer to the Japanese mainland our pilots were away more often. These were the times we were most vulnerable and Ben was hit hard a few times with bombs and kamikaze suicide crashes into the flight deck. Although he suffered some "bloody noses' and had to undergo frequent repairs the Japanese pilots couldn't land the big "knock out' punch.

But on the morning of March 19, 1945 - when Captain Lewis Gehres brought Ben in so close to the Japanese mainland that we were less than 60 miles off Japan's southern island of Kyushu - one enemy pilot got lucky. He sneaked past our radar and dropped two semi-armor piercing bombs that caught us with our pants down and Ben was in deep trouble. One bomb hit the flight deck dead center and tore through to the hanger deck where half of the ship's aircraft were being re-fueled and re-armed for the next strike against enemy shipping in Kobe Harbor. It ignited huge fires throughout the entire hanger deck and the fire spread to the deck below detonating tons of stored ammunition. The second bomb hit a bit further aft, pierced through two decks, and triggered more explosions from bombs and rockets that were meant for the enemy. As water poured in from cracked steel plates below sea level the engine room flooded and the ship lay dead in the water. Ben took on a 13-degree starboard list and we were in deep trouble. Explosions came from all over the ship and some members of the crew were blown over the side while others had to jump or be burnt alive. According to the scuttlebutt (gleaned from eyewitness accounts) some crewmembers were jumping over the side to avoid the fires while others were chucking the heavy drums of 20-millimeter ammunition over the side. These drums hit some of the men already in the water killing them. War and chaos often go hand in hand.

The official number of casualties on that day was 724 killed and 265 wounded and if it hadn't been for Lt. Donald Gary - the man I owe my life to - the dead would have numbered 1024. Three hundred of us had been in the mess decks, below the hanger deck, eating breakfast when the bombs struck and I was one of them. Normal access to the flight deck was via the hanger deck and there were only two exit ladders from the mess deck to the hanger deck. One was forward and the other was aft of the mess deck. I was with a group that ran to the forward ladder but fierce fire was shooting down from this deck which was just below the hanger deck and this exit was blocked. We ran to the aft ladder but smoke and fire also blocked this exit. We didn't know it at the time but the entire hanger deck was a death trap for anyone who went anywhere near it, and the deck below the hangar deck was almost as bad. The smoke was getting thicker every minute in the mess compartment that we were in so we all moved into the largest one. We 'dogged down' the hatch to try to keep smoke out while we picked each others brains to see if anyone knew of an unconventional route to get topside - no one did. During the first hour or so a few volunteers braved the smoke and fire to go on a scouting trip to find an escape path but only one man came back and he was bleeding so badly and so horribly burnt that he died within minutes of returning. We said a quick prayer for him and for the next two hours continued to pick each other's brains but to no avail. The engines had shut down and with no electricity we were in darkness. There was a tiny air-vent about the size of a tennis ball high up on the starboard side of the compartment we were

in and it gave a bit of light and air but water began to slop in as Ben's list worsened so things didn't look good for us.

We were in that compartment for three hours and I went over the 19 years of my life a dozen times thinking about the good times but every now and then had to come back to reality which was a numb acceptance of fate and a prayer that the end would be quick. One man 'lost it' and started shouting something about drowning like rats in a trap but he was dealt a dizzying clop alongside his head and when he regained his senses he was quiet. I guess we all had consigned our souls to either our maker or the devil when Donald Gary came on the scene. Apparently he had been topside when the bombs hit and knew that the hanger deck was alight from stem to stern and was a no-go area. He assumed that there would be men trapped below in the mess deck who would be unable to escape via the normal exits so he started thinking outside the square. He climbed up the island to a point where he could kick in a metal screen located on the smokestack. Ben had been dead in the water for about 3 hours and the smokestack had cooled enough for him to use the metal rungs inside it to climb down to the engine room. He made his way through the engine room and along a catwalk to skirt the water that had filled it and worked his way up through various hatches - hatches that none of us even knew existed - to the mess deck where we were trapped.

The smoke was getting thicker, the heat was getting more intense and the explosions were coming closer and with more frequency so we knew we had to move quickly. Gary had a battle lamp with him to light his way as well as breathing gear for himself, but a line of 300 men holding on to each other's belts and groping their way through thick smoke would be far too long. The men on the tail end of the line would not have survived breathing in the thick smoke for long periods so he divided us into three groups and made three trips. Despite the danger to himself he led each group down to the engine room and showed us the way into the smokestack. There we could climb up to the space where the metal screen had been, squeeze through it, and climb down the island to a point where we could jump down to the flight deck and join in the fight to save the ship. A few weeks later I returned to the compartment that we had been huddled in to revisit the scene. It was so twisted and distorted from the heat and the explosions that there's no doubt in my mind; we all would have died in there had it not been for Donald Gary. There is a lesson to be learned from all this and it applies to the men of all naval forces - know your ship well because your life or the lives of you shipmates may depend on it.

The fight to save Big Ben was hard. Radio operators aboard warships were more or less specialists. We focused on communications and lived in our own little world. We hadn't been trained to fight fires or perform any of the other duties that are part of the average seaman's life. Instead we copied code for eight hours and rested our heads in order to get ready for the next mind-numbing shift. But when I reached the flight deck and saw the condition of the ship I realized that if Big Ben sunk then I - along with the other men left on board - would go down too. I took a crash course in fire-fighting and unloading hot ammunition and this is where my gymnastic background came in handy - it was an incredibly exhausting task and having a healthy, strong body helped. In the meantime we were being towed by the Heavy Cruiser Pittsburgh (CA 72) while the rest of the task force formed a protecting circle around us. They threw up a barrage of anti-aircraft fire that served to discourage a batch of newly arrived Japanese planes that were piloted by some very excited Japanese pilots who seemed determined to finish the job. Our engines were dead which meant that our guns were not working and we couldn't fight back so all we could do was hit the deck and watch the action as enemy planes and bombs came so close that we wondered where they would hit. Thank heavens the gunners on our escort ships were good at their jobs. All the Japanese pilots that dived on us were shot down before they could finish us off.

In the next two days we managed to put out the fires on all decks and jettison all the hot ammo. The damage control crew worked furiously to pump the water out and make temporary repairs in the engine room. Finally Ben was able to get moving under his own steam and headed for safer waters. Then we started the grim task of collecting the dead from the many compartments of the ship. We formed a dozen two-man teams equipped with metal stretchers and worked non-stop until one by one they had all been found and carried to a part of the hanger deck that had been cleared for this purpose. The Chaplain collected their dog tags and their personal belongings, said a quick prayer over them, and had them dropped over the side. They had been dead for days and it was the only thing we could do to avoid disease. Other crewmembers went on a hunt for body parts and these were also given into the care of the Chaplain.

I was paired with another radio operator, Luke Burton, who in happier days had joined me for a few beers whenever we returned to civilization. I was still a very young-looking teenager and had trouble buying a beer in some places but we usually found a way around that. We may have broken the law but we felt that if a man can fight in a war he should be entitled to buy a few beers. Another one of my "liberty mates' was Norman (Dizzy to his friends) Dizak. Dizzy didn't make it to his twenty first birthday and the hardest thing that Luke and I ever had to do was to strap him on to our stretcher and bring him down to the hanger deck along with all the others for the Chaplain's attention. Luke and I must have hauled fifty or more bodies of our shipmates from all over the ship down to the hanger deck but bringing Dizzy to the Chaplain hurt the most. He was such a 'live wire'.

Everyone says that a dead body weighs more than a live one and I think it must be true. Big Ben had hundreds of watertight hatches that separated one compartment from another and they are not very big so Luke and I had to work closely together to maneuver the stretchers through them and up and down ladders on countless trips to the hanger deck. Dizek had been part of the midnight to 0800 watch in the main radio shack and happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time when he was killed. He had been a 20 year old from Chicago with lots of energy and a "life of the party' nature. He was popular with the radio crew and when we went ashore he was completely at home with the ladies. It was hard to believe he was dead and all that energy was gone forever. Why must it cost us so much to learn that war is such a terrible waste of lives - lives that really haven't had the chance to begin?

Another popular member of the radio gang was "Big John' Basham who stood more than 6 feet tall with considerable bulk but didn't have a mean bone in his body. Although he was a few years older than me he was like a big kid always dreaming up ways to break the monotony of long midnight to morning watches and bring a few laughs to the stultifying job of copying code day after day for the 8 hours of a radio operator's shift. His latest effort to break the monotony and put a smile on our dials was a competition to see who could cultivate the biggest and bushiest mustache. He won that event and the admiration of the entire gang with a big "fu-man-shu' job that no one could match. The irony was that although he survived all that the Japanese could throw at him including the bomb that killed "Dizzy' and so many others, he was killed a few months later by a New York City subway train while on liberty. He, too, was in the wrong place at the wrong time and his death made all of us think twice about human nature and the capriciousness of the "fine fickle finger of fate'.

My mind must have gone walk-about for a while during the unpleasant job of collecting bodies. For a second I lost focus and footing. Luke - who had hold of the front end of the stretcher and was pulling it up the ladder while I pushed - growled a few obscenities as he was pulled off balance. Like the rest of us he was dead tired and running on adrenaline and his usual good nature abandoned him temporarily. He called me a careless "bastard" but I managed to hold on to my own "Irish' temper and grunted out an apology. I tried to stay focused but my thoughts kept going back to Brooklyn, where I'd spent the first 17 and a half years of my life growing up and having fun.

As far as I was concerned "fun' was the joy of going to Ebbets Field to watch the Dodgers play baseball and 'willing' them to win. It also involved spending most of my time with a group of other kids who shared my interest in gymnastics and 'showing off' our skills while dazzling onlookers at the local playground. The ten-cent subway fare was hard to come by for most of us so in summer we found ways (mostly illegal) to get to Coney Island where we could "tumble' on the sand with other health nuts at Steeplechase Pier the home of the Brooklyn's 'muscle' men. In winter we kept warm in the Brooklyn Museum by pretending to be either music-lovers who enjoyed the concerts of classical music that were performed every Sunday afternoon, or kids who were interested in ancient relics and artifacts. The concerts were performed for the benefit of the more sophisticated adult audiences and we noted with a cynical smile how some of the older members of the audience snoozed through the event. Did these 'oldies' go to these events because they felt the need to be part of a crowd? Were they just lonely people?

While the younger and more affluent older women showed off their luxurious fur coats and new hair-styles we were busy arranging "accidental' meetings with some of the teen-aged local females that were in the process of becoming young women. When we were "in the money' we spent our Friday and Saturday nights at Karp's ice-cream parlor with the girl of our choice and listening to the jukebox as it played the music of Glenn Miller and Artie Shaw. Frank Sinatra was becoming more popular than Bing Crosby despite his 4F status but both crooners set the stage for romance and I have them to thank for some of the warmer and more enjoyable romantic interludes with the female species.

Pearl Harbor had changed all that and I became one of the many Americans caught up in the nationalistic fervor that gripped the nation. Those who joined the U.S. Naval Reserve during war time committed themselves to serve for the duration of the war plus six months and I convinced myself that I had volunteered to serve in order to help Uncle Sam teach the Japanese a lesson they would never forget. After years of honest reflection I finally admitted to myself that the prospect of adventure was just as persuasive as the air of patriotism that the Jap "sneak attack' had generated in most Americans. To a seventeen-year old boy the idea of taking part in a war is often seen as an exciting adventure. But harsh reality soon changes the sense of adventure to a realization that war is a deadly serious business and people - both combatants and non-combatants - are going to get hurt. Some will be crippled for life and some will die, and their death will usually be under very unpleasant circumstances. While the adventure of war can make the adrenaline run riot and enhance the feeling of being alive, it can also result in physical or psychological damage that can influence the course that young lives take and the damage can stay with them for many years - perhaps forever.

One can return from war crippled not only physically but mentally as well. I was one of the lucky ones that came out of the war with only a few scratches but I still have some memories I'd rather not have. And it was years before I could bring myself to eat fish because even today - in my mind's eye - I can still see shipmates that had been committed to the sea floating on the surface after their bodies hit the water - men that were destined to be fish food. They had been dead for days and had begun to decompose so there was no time for the traditional burial ceremony or even to weigh them down. In fact the "floaters' were so many that we were asked by our escort ships to wait until nightfall before dropping them over the side. The sight of so many bodies was considered bad for the morale of the crew of the escort ships. How ironic! We were concerned about disease while they were worried about crew morale - how quick we are to close our eyes to the nasty realities of war.

While Luke and I went about our grisly task of collecting bodies my mind kept wandering. A self-defense mechanism? Perhaps it was. We had found Dizzy in a corridor near the main radio shack. He had died sitting up - in an almost fetal position - with his knees drawn close to his chest, his arms around his knees, and his head resting on them. There were no visible wounds and he wasn't burned but there were a few trails of blood coming from his nose and ears so we assumed that concussion was probably the cause of his death. Rigor mortis had set in and he was so stiff and inflexible that we had to put him in the stretcher sideways, still in a fetal position. I remember thinking at the time that it was an undignified way to leave this world. Our later experiences with finding and collecting more of our dead shipmates brought home to me the fact that there is no dignity to be found in any violent death. In some cases we had to pry bodies loose from desperately sought refuge in unbelievable places. One poor soul had somehow managed to jam his head under a metal clothes locker which stood on a low platform that left a gap of only about 12 inches of space between the bottom of the locker and the steel deck. His arm was locked around a leg of the platform and I had to pull him out by his feet while Luke unlocked his arm from the locker leg. Another had been lying in water for two or three days and was either very water-bloated or had been a huge man who outweighed both Luke and I together. We had to get help from another team to get him to the hanger deck. On our way to the gathering point we had to pass through a part of the hanger deck that had not yet been cleared by other crews. It was filled with about two feet of ashes of an unknown nature amongst which there was the occasional head-less and leg-less burnt torso. Among other bits of human remains I saw a blackened shoe with a foot still inside it. I had to ask myself why these parts of the human body hadn't been reduced to ashes when the heat of the fire had been so intense that airplane engine blocks had been welded to the steel hanger deck.

My next thought was that a few weeks ago I'd had my 19th birthday and the fates had belatedly given me the gift of life. Life becomes so much more precious when death is all around and such a gift is hard to top. I reckoned I had used up a lifetime of luck in one day so to look for more in later life would be foolish. Not long afterward another thought hit me. If I hadn't been such a greedy-guts and decided to go to breakfast early on that morning (breakfast on a ship that had been at sea for long months is not hard to pass up) the chances are I would have been killed. As usual I would have been standing on the long queue that often extends from the hanger deck down to the mess deck and would surely have been on the hanger deck when the "big bang' happened. The blast would have caught all of the crew that were working on refueling and re-arming of aircraft as well as those who had been standing in the chow line. The combined effects of thousands of gallons of aviation fuel bursting into flame and the explosions of tons of ammunition would have killed them instantly.

When I - along with the rest of Lieutenant Gary's "rescuees' - reached the flight deck it was a hive of activity. There was a huge hole in the flight deck near the Island and thick plumes of smoke were coming out of it and darkening the sky. Explosions kept coming from the hanger deck below and threw debris up through the hole with tremendous force. Our giant radio antenna was down in the horizontal position to accommodate aircraft takeoffs and this made it hard for escort ships to get alongside and help with fighting the fires or evacuating the wounded. We tried to use a manual crank to get the antenna upright but it wouldn't budge so a heavy cruiser tried to pry it loose. But the harder the cruiser pushed the faster we went around in counter-clockwise circles. We finally had to give up and placed a long wooden plank between Ben and a ship that came alongside to transfer the badly wounded to relative safety where they could be treated. We later heard that one man crossing over had lost his balance, fallen into the sea and had been crushed between the two keels.

A portable generator was going full blast on the flight deck and this made it possible for sea-water to be pumped up to the flight deck. I joined a crew of about ten men who were controlling and directing the hose while edging ever closer to the hole in the flight deck in order to try to cool down the fires on the hanger deck. It was like trying to control a giant powerful snake and with the wind shifting every few minutes we all had a blanket of heavy, choking smoke in our faces most of the time. The men who held the nozzle end of the hose lasted only a few minutes and had to be dragged out of the smoke before they lost consciousness and fell into the hole so we worked out a system of alternating positions. The nozzle man would hang in there for two or three minutes and then move out to the end of the line to clear his lungs and breathe fresh air while the next man moved up. This continued for a few hours until another crew took over and we were sent to search for and dump hot ammo.

Ammunition was stored in various compartments all over the ship and we found piles of five-inch shells that were very hot but could still be handled with protective gloves. We formed lines of men going from these stacks and up ladders to a point where the ammo could be jettisoned. A five-inch shell weighs about forty or fifty pounds and when it must be hand-carried along a sloping deck that is wet, and passed along a long line of men that winds across decks and up ladders it can be a tricky situation. Physical exhaustion and the possibility of someone slipping on the deck and dropping one of the shells was a worry because none of us knew what would happen if a hot shell was dropped onto the metal deck. The thought had no sooner crossed my mind when damned if it wasn't me that slipped and dropped one that landed right on its nose. With my heart in my mouth I scooped it up and tossed it to the next man in line who caught it with a look of horror on his face. With a shout of "hot one' he tossed it to the next man and I guess that shell reached topside in record time. Since it was polite enough not to explode we all felt a bit less anxious when the inevitable happened and more were dropped. .

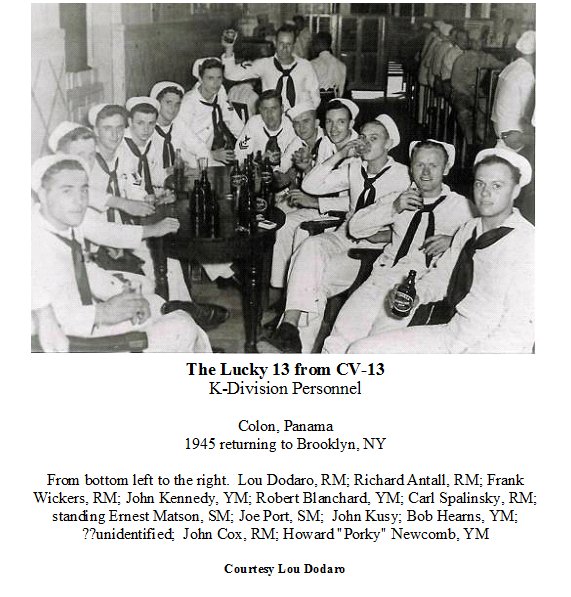

With all fires out and hot ammo disposed of we took a short break for a much needed rest. At times like these it was usual for shipmates to exchange news and views if they can stay awake. During the gabfest there was general agreement that Big Ben was a great ship that was virtually unsinkable but unlucky. Ben had suffered battle damage four times in the last 10 months and each time the damage got worse and the number of casualties increased. Some of the crew thought that the huge number "13' painted on the flight deck both fore and aft was an irresistible challenge to the fates and this was why Ben was so unlucky. I didn't agree because I was one of the lucky 704-crew members left aboard the ship that he carried safely home.

After inspection by the top brass the ship was given some additional temporary repairs. With order restored out of chaos we headed for the island of Ulithi - previously held by the Japanese - for a few more temporary repairs and restocking of the food and other essentials. Then we were off to Pearl Harbor for inspection by the bigger brass and then on to the Brooklyn Navy Yard where the experts would decide if Ben could be repaired or was damaged beyond repair. Our arrival at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu was an event to be remembered. It was a naval tradition that when a damaged American warship arrived in port it was met with lots of attention. Top naval officials and community "big shots' were part of our welcoming committee along with the military band of the naval station. The band of the Pearl Harbor Naval Station was magnificent. We were greeted with a booming version of "Anchor's Aweigh' that was played with professionalism and with a volume that made our ears ring. We were assembled on the flight deck to receive this honor and were impressed by the enthusiasm of the welcoming committee.

It was also traditional for the ship's band to reply with its own version of "Anchor's Aweigh'. It's just a way for one friend to say "welcome home' and for the other to say "thanks, glad to be back'. I don't know if Ben had ever boasted a real ship's band but we managed to assemble a rag-tag group of amateur musicians who may have had doubtful musical talent but were blessed with strong spirit. They had scrounged up a few brass instruments and a drum that had somehow survived the fires. We were proud of their enthusiasm but our response was so weak in comparison that it was either pitiful or laughable depending on the listeners' viewpoint. It was like answering a 20-gun salute with a .22 caliber pistol and while some of the crowd may have felt pity, most of the crew thought it was great. We were all desperately in need of a laugh and many were the smiles that began to appear on worn and tired faces. It was just the tonic we needed and this is one of the nicer memories that have stayed with me for more than fifty years. We then headed for the Brooklyn Navy Yard and arrived on the 28th day of April 1945.

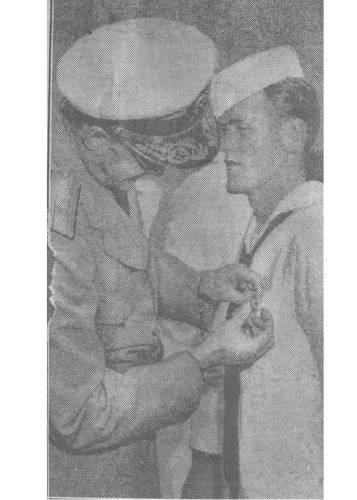

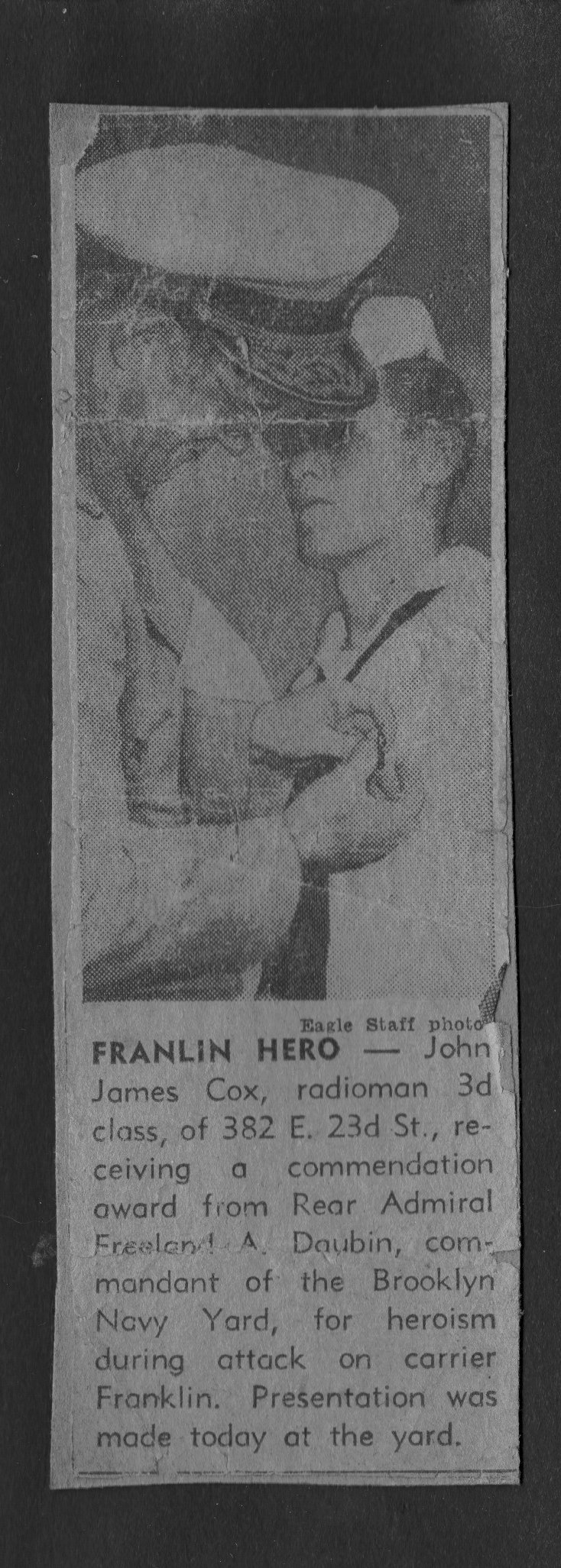

Brooklyn is one of the Boroughs of New York and my birthplace so I had family and friends there and was happy to see it again. We were met by hordes of dignitaries, high-ranking naval officers, reporters and photographers. Being a native son I shared a tiny bit of the interest that surrounded Big Ben and was amazed to find my photo in one of the local newspapers under the heading "Local Boy Returns'. When Mom saw her youngest son's photo in the paper she was "tickled pink' and promptly showed that she had a nose for a potential profit. Without asking my permission she made a deal with another local paper of the time - the Brooklyn Eagle - and promised them that she would deliver me for a personal interview. At first I was annoyed and refused but Mom was a very persuasive mother and she always managed to make me see her side of things. I finally agreed and it was typical of her that she would never tell me how much she had been paid for her bit of opportunism. Well, she'd had to scramble for a buck all her life to bring four kids up by herself so who could blame her? Certainly not me!

Ben was later opened for inspection to the curious public. The ship was given lots of attention by the news media, and its crew was awarded four battle stars along with a commendation ribbon. The Franklin had played an important part in the united effort to defeat Japan but after a war there is always "Monday-morning quarterbacking' and many questions emerge regarding the course of events and the correctness of the decisions of those who were paid to make them. The main criticism surrounding Big Ben was the wisdom of bringing an aircraft carrier so close to the enemy mainland that it took only ten minutes of flying time for enemy pilots to find and attack it. Japan was in dire straits in March 1945 and Japanese pilots were desperate to stave off defeat so they crash-dived on every enemy ship they could find and aircraft carriers were prime targets. Bringing Big Ben in close to Japan's mainland would have given our pilots an extra ten minutes over their targets but was the extra time worth the ultimate cost? Was Captain Gehres a hero when he risked the safety of the ship along with his own life and the lives of his crew by bringing his ship in so close to the enemy shores? Or was he an ambitious man who wanted to win approval from his superiors and enhance his reputation as a daredevil by being the only captains during war time to bring a major warship like an Aircraft Carrier to within fifty or sixty miles of Japan? Was he a hero or an ambitious fool

He was not well loved by the crew. Many of us saw him as an arrogant man who in quiet times roped off half of the flight deck so that he could have a sun-bath while being safe from the eyes of the crew. He used his marine guards as "go-for's' to bring him drinks and refreshments from his cabin and the galley; and he never went anywhere on the ship without his personal marine bodyguards. Whenever the Captain of a major warship went ashore it was tradition for it to be announced over the P.A. System "Here this - the Captain has left the ship". It was not unusual for this announcement to be met with a muted 'hurray' when Captain Gehres departed. Unfortunately his arrogance was contagious and many of the higher-ranking commissioned officers followed his lead so the relationship between the crew and their commissioned officers was not always a good one. One Lieutenant Commander who was in charge of the crews that manhandled the planes from one spot to another on the hanger and flight decks (we called these guys "airdales') was famous for his verbal abuse of his crew. During an early morning GQ (General Quarters) when the crew ran to their battle stations (in the dark) he disappeared over the side. Luckily he had a life jacket on and was picked up later by a Destroyer Escort (DE). He reported that an unknown person had 'bumped' into him on the way to his battle station sending him into the drink. The scuttlebutt (gossip) was that it had not been an accident and in light of the fact that his behavior was much improved after his return to the ship the scuttlebutt was probably right.

Unburdened with an answer to the question of whether Captain Gehres was a 'hero' or a 'villain', I was pleased to receive an honorable discharge from the Navy on December 7, 1945 four years to the day of the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor - an odd coincidence. I decided that military life was not for me and said "thank you but no thank you' to offers of a re-enlistment bonus and a promise of rapid promotion if I would stay on. Like many other young men who had been part of a shooting war I decided that war should be outlawed and diplomacy should be the way to settle differences between nations. As far as I'm concerned war is really a failure of diplomacy and/or an inability or unwillingness to negotiate a mutually acceptable compromise. One of the tragedies of war is the fact that it's the young men on both sides who pay for this failure of diplomacy with their lives and their limbs, while the "failed' diplomats – physically, mentally, and psychologically untouched by war - continue to live and enjoy all the benefits that high political status brings. War costs millions of people, both military and civilian on both sides, their lives and their limbs while those who profit from it, including manufacturers of munitions, laugh all the way to the bank. The three highest earning businesses in most advanced societies are oil, munitions, and drugs and this is a fact that so-called civilized people should be ashamed of. It has to change

American veterans of World War II were not offered psychological counseling, as were the veterans of the Vietnam conflict. They were dumped back onto 'civvy street' with their bad memories intact, the forced indifference to, and acceptance of, death still a part of their psyche, and the calluses - that they needed to grow on their hearts if they were to be able to continue to function - still in place. I guess I went a bit wild in this "sink or swim' environment that emerges when governments ignore the adverse psychological effects that war has on relatively "normal' people (whoever they are). I tried hard to make up for the lost years of young adulthood by becoming a leading exponent of the "eat, drink, and be merry' set. From the vantage point of an extra half-century of living I've concluded that when young people see, and become part of, such a terrible waste of human lives they often adopt a mental set that says '"life is short so let's enjoy it to the full while we can."

i Was 17

By John J. Cox

By John J. Cox